Sacred Art: Daoism and the Art of Non-Action

Highlighting nature and serenity, Daoist art seeks to accept life as it is, and embrace that it is not just about transcendence

Abigail Leali / MutualArt

Apr 17, 2024

How are we, as humans, meant to live together? Every culture has asked this question, and countless philosophers and politicians have offered their answers. From Plato’s Republic to Thomas More’s Utopia, to modern observations from sociologists and economists, the West has a long tradition of sociopolitical idealism. We strive towards a “perfect” world without violence, tyranny, or greed. It’s evident in our cultural determination to hold those in power accountable, institute systemic reforms, and promote justice among individuals. Though perfection – of course – eludes us, this attitude has helped, in part, to grant legitimacy to the democracy of Athens, the Roman Republic, medieval kings and their revolutionaries, and our current globalized order.

But driving for constant change is not the only response to this question, nor is it always the best. Chinese thinkers, too, have deliberated about how to structure society over several thousand years’ worth of dynasties, each with their own conflicts, alliances, wars, and intrigue. Presented with the same human nature, China took a very different approach to that of the West. Whereas Western governments tend to live and die (and die they often have) by their ability to protect and serve those in their care, “China” has, at least as a concept, remained unquestioned for millennia. Even in periods of significant change and reform, the Chinese people have remained committed to their shared social identity; rather than searching for some elusive utopia, they have worked to guard, maintain, and nurture the tradition they already have. Certainly, this commitment has, at times, led to great involuntary human suffering, just as Western ideals have in Europe and beyond. Still, the relative stability of the Chinese culture has provided its people with a unique opportunity to adapt to the world as it is, rather than as they may wish it to be.

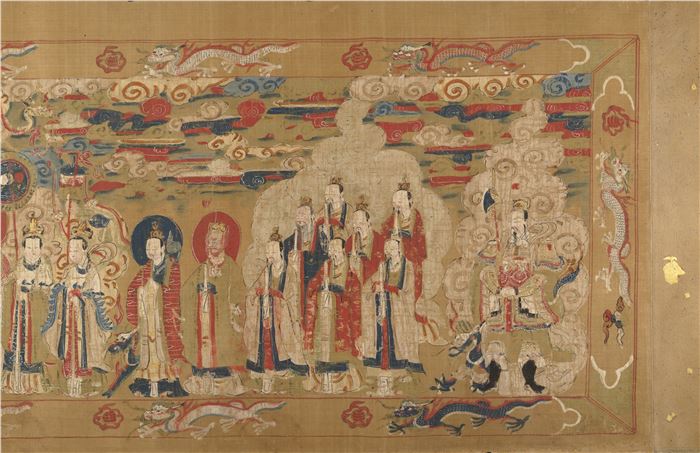

Canonization Scroll of Li Zhong, colophon dated 1641.

Canonization Scroll of Li Zhong, colophon dated 1641.

Confucianism is one of the results of this unique environment, establishing guidelines for effective social action and peaceful living under Chinese rule. But if Confucianism is an art of action, then Daoism is its contrary and complement: the art of non-action. Instead of emphasizing our power to contribute to society, it acknowledges our equal capacity to commune with and be changed by it.

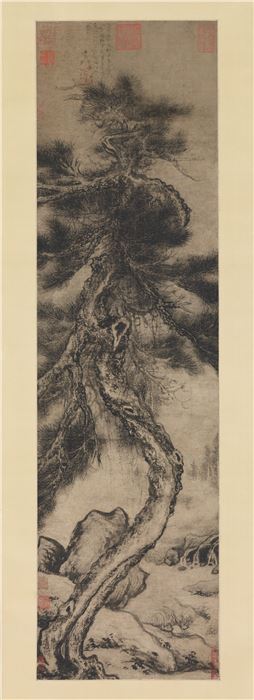

On the surface, art produced by the Daoist tradition can seem similar to that of Buddhism: both highlight nature and simplicity, pervaded by a sense of quiet tranquility highlighted through unassuming swathes of negative space. Artists carefully observe the patterns and textures of the natural world, bringing them into being through ink and pigment. Both serve as a counterbalance to Confucianism’s concern for public life, celebrating beauty and introspection. The distinction between the two becomes clear primarily in the philosophies themselves. While Buddhist art depicts nature to transcend it, Daoist art does so to embrace it.

Wu Boli, Dragon Pine, late 14th-early 15th century.

To put it loosely, Daoism and its art fill a similar niche in China to that of Shinto in Japan. Both are native, localized religions that persist despite the overwhelming influence of their larger philosophical neighbors. Though they have their admirers and even adherents from afar, they are intrinsically tied to their place and people. In this role, they serve to ground, in a way, their respective cultures, keeping society from straying too far into the potential excesses of political or spiritual life. They are a retreat into nature — a reminder that our lives, at least on this earth, are not and cannot be exclusively a matter of searching for the transcendent.

What is most unique about Daoist art is the serenity with which its artists — and practitioners, for that matter — accept the world exactly as it is. As its name proclaims, Daoism is meant to be “the Way.” It acknowledges the reality of evil in society, in nature, and in individuals. It accepts the bad alongside the good, allowing both to flow through life like water down a stream.

Fang Congyi, Cloudy Mountains, c. 1360-1370.

Fang Congyi, Cloudy Mountains, c. 1360-1370.

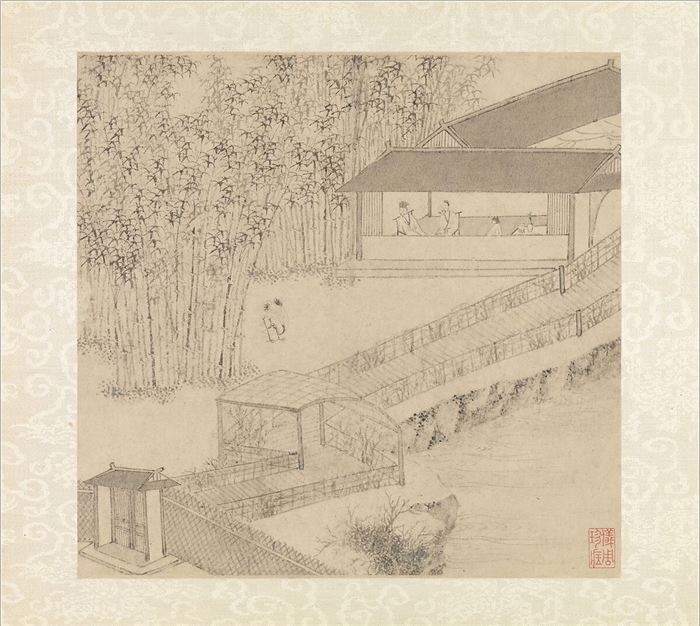

Perhaps this perspective may seem fatalistic — which is undoubtedly a potential pitfall. But in Chinese society, in which war and politics seem to have incited a nearly endless frenzy of struggle and ambition within the confines of an immortal State, it can be a soothing balm for the soul. Take even our Confucian artist, Wen Zhengming. In his painting, The Garden of the Inept Administrator, he takes refuge from political failure in Confucianism’s social ideals. But the administrator’s retreat into nature also reflects an innately Daoist instinct: one that allows nature to reveal our place in the world rather than us imposing ourselves upon it.

Wen Zhengming, det. Garden of the Inept Administrator, 1551.

Wen Zhengming, det. Garden of the Inept Administrator, 1551.

To live in any society, Daoism seems to suggest, it is necessary to accept and embrace that which does not meet our ideals alongside that which does — both are part of the same whole, and both contribute to life in their own way simply by existing. Even the Daoist heavenly hierarchy reflects earthly bureaucracy, ruled by the Jade Emperor, who oversees hordes of gods collaborating in their various forms of work. Just like a real bureaucracy, it has its inefficiencies; important tasks and projects from time to time slip through the cracks. There are moments of harmony and of conflict, of synchronization and of miscommunication, of clarity and confusion — just as there are in our own mundane reality.

%2c%20outing%20to%20zhang%20gong%e2%80%99s%20grotto%2c%20c.%201700.jpg) Shitao (Zhu Ruoji), Outing to Zhang Gong’s Grotto, c. 1700.

Shitao (Zhu Ruoji), Outing to Zhang Gong’s Grotto, c. 1700.

Still, in Daoist art, we see that accepting life for what it is can, paradoxically, bring about its own kind of utopian peace. Just as nature thrives on the circle of life, which requires death to bring about rebirth, so, too, can we humans accept the inevitable failures and foibles of those around us as a key, even beautiful, part of existence. Surely, dreaming of better social systems or working hard to achieve them isn't wrong. But as we reflect on what it means to live together, Daoist art serves as a happy reminder that it is always a futile endeavor to bring about peace through strife. It may be that only when we accept our individual moments of suffering, do we become capable of bringing about a better world.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page